“It has been in almost continuous performance since 1742, when it premiered,” said author Charles King. “It’s absolutely everywhere. And you can’t really say that about any other piece of serious music.”

CBS News

The King’s New Book, “every valley” (Double Day), gives us the back story of “Messiah” and his “Hallelujah Chorus,” which comes about two-thirds of the way through Handel’s oratorio. “It’s not the final!” said the king. “People start getting ready to go out, you know, grab their keys and their parking validation, and then it’s like, ‘No, sit down. There’s a third of this thing left!’ ‘”

“Messiah” was not actually Handel’s idea. The words came from a friend named Charles Jennings. King suggested that it should really be called the “Messiah” of Handel and Jenness.

“Charles Jennings was a wealthy landowner, but he also suffered from this kind of doom and gloom — what we might now call chronic depression or bipolar disorder,” King said. “He starts pulling books off the shelf, and he starts copying passages of scripture. He was also, I think, developing a philosophy for living.”

Conductor and author Jane Glover has conducted “Messiah” more than 100 times (most recently, this month at Trinity Church in New York City). “I never fail to take my hat off, actually, to Charles Jennings for putting it together,” he said. “Messiah” is in three parts. The first part is the Christmas story, which is why everyone does it at Christmas. The second part is the crucifixion, but then also the resurrection. And then Part III is about salvation. Therefore, this three-part speech is a powerful form.”

In the 1720s and ’30s, Handel’s famous Italianate operas made him a musical megastar. But in the 50s his popularity was waning. So, when he was invited to a series of concerts in Dublin, King said, Handel thought he could restart his career: “And so, he sat down with the text he had from Charles Jennings. received and decided he would try to make something. ‘Hmpf, what am I going to do with them? I’ve got the Bible verses in the wrong order?’ But he does.”

In his book, King describes the final product as “weird.” “This is Weird,” he laughed. “It’s the weirdest thing Handel ever did.”

Handel wrote the three-hour piece (for chorus, soloists, and nine-piece orchestra) in 24 days … 260 pages of music!

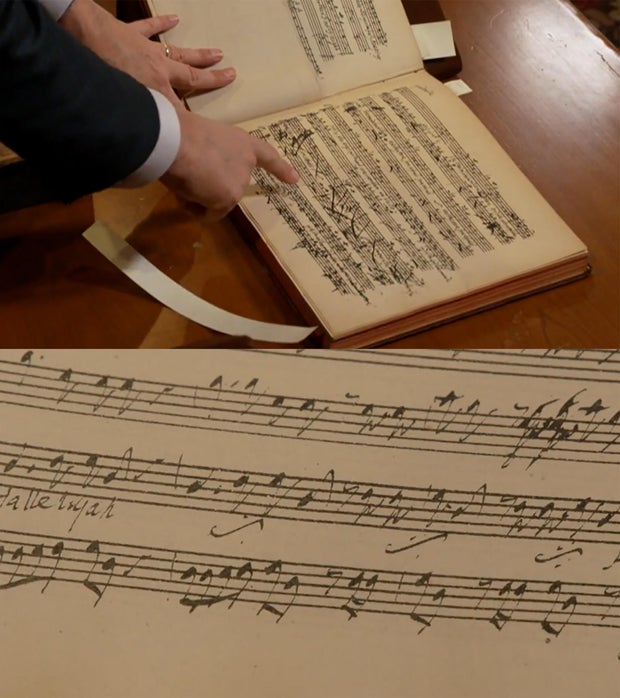

At the Morgan Library and Museum in New York, music curator Robin McClellan showed me a copy of Handel’s original score. “It shows the speed at which he wrote. It’s so dirty!” McClellan laughed. “He was really concerned about getting his ideas down on paper as quickly as possible.”

For the “Hallelujah Chorus,” Handel wrote the word “Hallelujah” once … and then used the standard jazz repeat sign that we still use today! “He’s writing the musical equivalent of ‘et cetera, et cetera, et cetera,'” King said. “In that era, there was really no presumption that anything would ever be done again.”

CBS News

“Messiah” was a huge hit in Dublin, and eventually, in London. It seemed to offer a sense of hope and light at a time when these were in short supply.

King said, “‘Messiah’ was born as a dark shadow of the Enlightenment. Britain was at war, with a 75% infant mortality rate in London. And so, ‘Messiah’ is a kind of art. What basis is it arguing, what possible basis for hope can there be when you have all this evidence Who would suggest otherwise?”

Almost everyone liked it – except Charles Jennings! “He was worried that Handel had done a kind of cheap job,” King said. “He says, ‘I will never repeat my words to Handel to be so abused!'”

Handel agreed to make some changes, and Jenness relented. “Finally,” King said, “he wrote to a friend that he thought it was ‘an important, fine composition.’

“Messiah” came to the American colonies in 1770, six years before it was also a country. It was performed at Trinity Church in New York City, the very same hall where the sound was played this month.

Trinity Church

Over time, “Messiah” has changed in all sorts of different ways. Handel’s nine-piece orchestra gave way to thunderous musical forces. Different terms were applied. “People sitting in hard pews in church don’t want to sit here for three and a half hours,” Glover said.

And the entire section was demolished. “Some people just do Part I at Christmas; that’s a great way to do it,” Glover said.

Yet, in all its versions, Handel and Jensen’s masterpiece has delivered the same message for nearly 300 years: that there is always hope.

“Each generation that has heard it has felt that this music is like a message in a bottle for them,” King said. “It’s a piece of music that does stuff for us.”

His message? “Have the possibility of hope; problems can be solved; the world is going to get better. And then, take it and make it happen.”

For more information:

Story prepared by Sarah Kugel. Editor: Carol Ross.